In 1781, a young French woman named Marie-Jeanne Philippon married wealthy businessman Jean-Marie Roland, thus becoming known as Madame Roland.

Madame Roland and her husband were early supporters of the democratic goals of the French Revolution.

They became active leaders of the progressive but moderate pro-democracy party called the Girondists.

The Girondists supported changing France’s political system from an absolute monarchy to a more democratic constitutional monarchy, like England’s.

Unfortunately for the Rolands — and for French King Louis XVI and many other French citizens — a much more extreme group took control of France a few years after the storming of the Bastille.

They were called the Jacobins and were responsible for the infamous “Reign of Terror.”

During that bloody period in 1793 and 1794, Maximilien Robespierre and other Jacobin leaders imprisoned and executed tens of thousands of French citizens.

The victims included members of aristocratic families who had benefited from the previous monarchical system, open or suspected supporters of Louis XVI, and advocates of any future monarchical system.

Others were killed simply because top Jacobins viewed them as political rivals or disliked them.

When the Rolands publicly criticized the worst excesses of the Reign of Terror, the Jacobins responded by ordering their arrest for “treason.”

Madame Roland was arrested and imprisoned in Paris in the spring of 1793.Her husband Jean-Marie was traveling at the time.

When he heard his of wife’s imprisonment, he went into hiding.

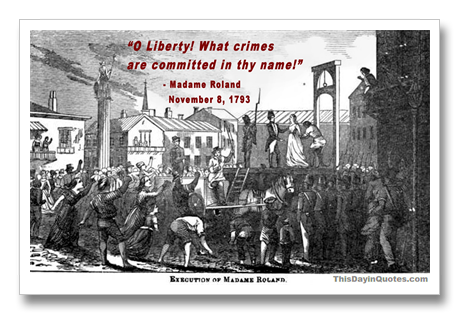

On November 8, 1793, after months in prison, Madame Roland was sent to the guillotine, a few weeks after Marie Antoinette met the same fate.

On the way to her execution, Madame Roland passed a large statue of the Goddess Liberty that her former political comrades had erected nearby (the same goddess portrayed by the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor).

According to historical accounts of the day, when Madame Roland saw the statue she looked at it sadly and made a remark that’s included in many books of famous quotations:

“O Liberté, que de crimes on commet en ton nom!” (“O Liberty! What crimes are committed in thy name!”)

Shortly after saying these words, Madame Roland was beheaded.

After Jean-Marie Roland heard of his wife’s death, he wrote a suicide note that said: “From the moment when I learned that they had murdered my wife, I would no longer remain in a world stained with enemies.”

He attached the note to his chest.

Then he ran his cane-sword through his heart, becoming another victim of the Reign of Terror.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Email me or Post them on the Famous Quotations Facebook page.

Related reading…