In the years leading up to the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775, the rebel-rousing Sons of Liberty used an engraving of what they called “The Boston Massacre” to encourage anti-British sentiments.

The engraving, done by Paul Revere, shows a line of British soldiers coldly firing their bayoneted muskets into a crowd of Americans, several of which lay bleeding on the ground.

A poem underneath that scene describes how the King’s men “With murderous Rancour stretch their bloody hands, Like fierce Barbarians grinning o'er their Prey.”

It was good propaganda. But it did distort what happened at the “Boston Massacre” on the night of March 5, 1770.

That night, a local resident got into an argument over a debt with a British soldier. Eight other British soldiers came out on the street to help their comrade. A group of Americans surrounded the soldiers. The Brits were soon being yelled at and pelted with snowballs, ice chunks and debris by the much larger, hostile crowd.

The bloodletting appears to have started when a mulatto seaman named Crispus Attucks hit one of the soldiers with a piece of wood. The soldiers panicked. Somebody yelled “Fire!” and they shot into the crowd, killing Attucks and four other Americans.

When the British soldiers were arrested and put on trial for murder, a Boston merchant asked local lawyer (and future president) John Adams to defend them. He agreed, knowing it would make him unpopular and could ruin his career.

Adams believed the soldiers deserved legal representation as a matter of principle. After looking into the incident, he also believed they were provoked and should not be executed for murder, as many Bostonians wanted.

On December 4, 1770, the second day of the brief trial, Adams gave his summation to the jury.

He argued that anyone might have reacted the same way the soldiers did in such a confusing and potentially life-threatening situation. He suggested Crispus Attucks was more to blame for “the dreadful carnage of that night” than the soldiers, because of his “mad behavior.”

“Facts are stubborn things,” Adams said, uttering what became a famous quotation. “And whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence: nor is the law less stable than the fact; if an assault was made to endanger their lives, the law is clear, they had a right to kill in their own defence; if it was not so severe as to endanger their lives, yet if they were assaulted at all, struck and abused by blows of any sort, by snow-balls, oyster-shells, cinders, clubs, or sticks of any kind; this was a provocation, for which the law reduces the offence of killing, down to manslaughter.”The jury was persuaded. Six of the soldiers were acquitted. Two were found guilty of manslaughter and punished by having their thumbs branded.

Several years later, John Adams wrote in his diary that his defense of those British soldiers was “one of the best Pieces of Service I ever rendered my Country.”

“Facts are stubborn things” became one of Adams' best known and oft-cited quotes. However, contrary to what I once thought, he didn't coin that line.

As noted by quote mavens Garson O'Toole on his Quote Investigator site and Dr. Mardy Grothe in his Dictionary of Metaphorical Quotations, it was already a saying in England and America and dates back to at least the early 1700s.

Two centuries later, President Ronald Reagan uttered the most famous modern use and perceived “misuse” of that quote.

It came in his speech at the Republican National Convention in New Orleans, Louisiana on August 15, 1988.

Reagan was there to speak in support of the current Republican presidential candidate, his Vice President George H.W. Bush, who was running against Democrat Michael Dukakis.

In the speech, Reagan recounted what he viewed as the successes of his administration and the reasons why he felt voters should elect another Republican as president.

Reagan repeated John Adam’s facts quote several times in the address. It was a rhetorical device he used in the part that focused on the economic problems he blamed on his Democratic predecessor, President Jimmy Carter.

“Before we came to Washington,” Reagan said, “Americans had just suffered the two worst back-to-back years of inflation in 60 years. Those are the facts, and as John Adams said, ‘Facts are stubborn things.’ Interest rates had jumped to over 21 percent…Facts are stubborn things…The median family income fell 51/2 percent. Facts are stubborn things.”Then he made what became one of his most-cited gaffes, saying:

“Fuel costs jumped through the atmosphere, more than doubling. Then people waited in gas lines as well as unemployment lines. Facts are stupid things.”Reagan immediately corrected himself, adding: “Stubborn things, I should say.” But once the word stupid came out of his mouth, that’s the version that was picked up and cited by his critics.

Today, thousands of websites quote Reagan as saying “Facts are stupid things” as if it were somehow a significant quote — without noting that it came from a speech in which he said “stubborn things” several other times and quickly corrected his brief slip of the tongue.

Of course, thousands of others note that Reagan said “Facts are stubborn things” — without mentioning that he was quoting John Adams, thus creating the impression that Reagan coined the line.

When it comes to quotations on the Internet—and to politics—facts are often slippery things.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Questions? Email me or post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page.

Related reading and viewing…

You probably know the famed

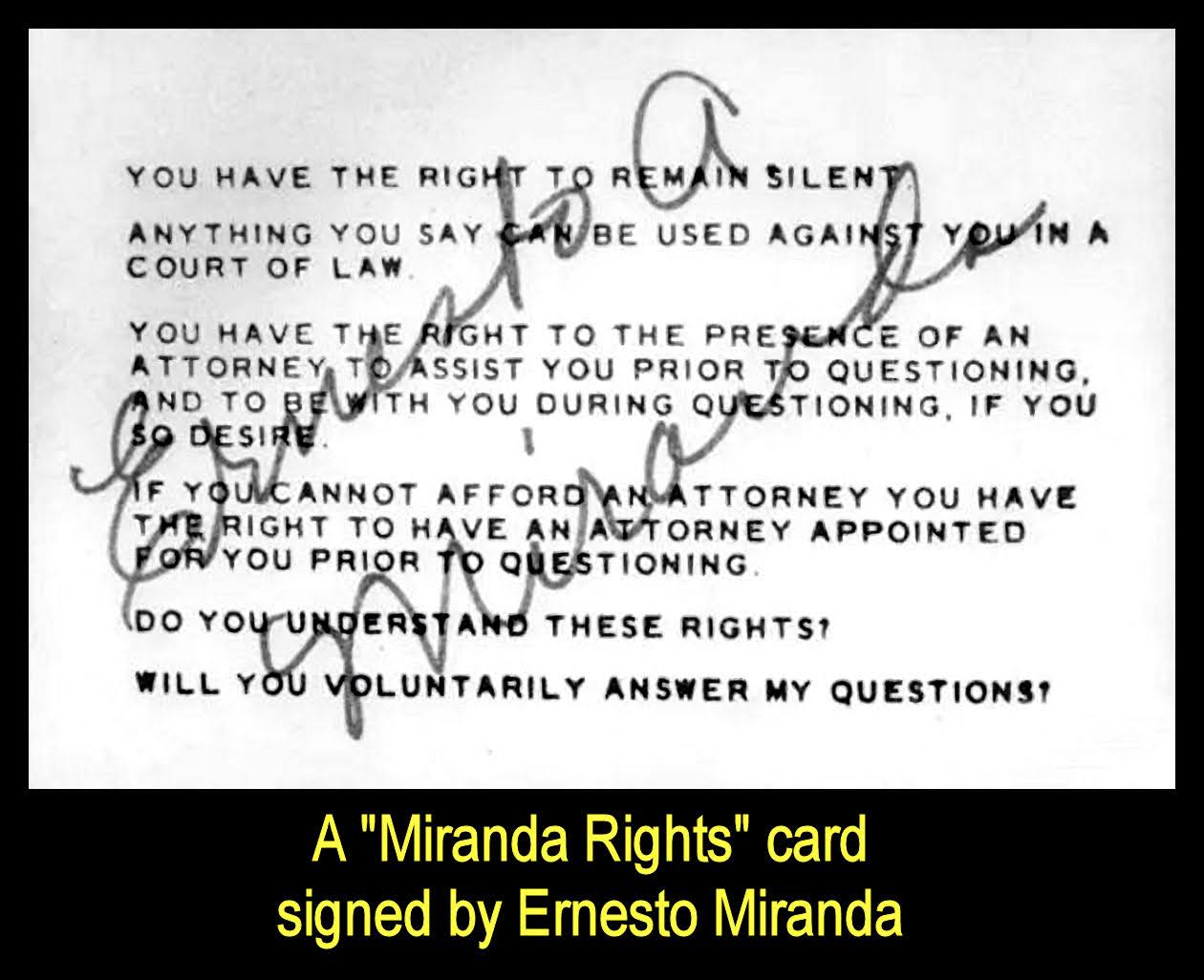

You probably know the famed  Miranda v. Arizona was appealed up to the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices ultimately ruled that Miranda’s rights had indeed been violated. The court’s decision included a section that became the basis for what was soon being called “Miranda Rights.”

Miranda v. Arizona was appealed up to the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices ultimately ruled that Miranda’s rights had indeed been violated. The court’s decision included a section that became the basis for what was soon being called “Miranda Rights.”

What about the tear-jerking line by the crushed kid?

What about the tear-jerking line by the crushed kid?