Some observers have expressed surprise that two populist, anti-establishment candidates who many people view as “extremists” won sizeable percentages of the votes in the 2016 presidential primary elections.

But in the past there have been other high profile populist presidential candidates who based their campaigns on disdain for “the establishment” and passionate opposition to something.

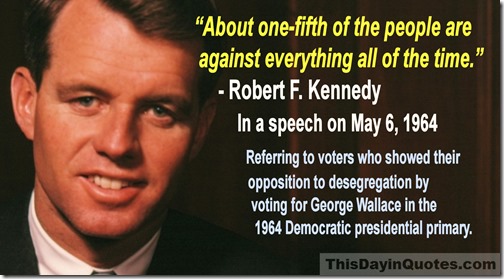

In 1964, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy uttered a oft-cited political quotation that is a reference to this phenomenon, though the connection is not widely known.

Speaking to a group of law students at the the University of Pennsylvania on May 6, 1964, Kennedy observed:

“About one-fifth of the people are against everything all of the time.”

This quote (often given without the word “About”) is found in many books and on many websites, usually without any explanation of the context.

Unfortunately, as far as I know, the speech is not posted anywhere online.

However, there is an old news story in the Google News Archive that sheds light on why Kennedy made the remark.

It’s a brief Associated Press article about the speech that ran in newspapers later that week.

The article notes that Kennedy was commenting on the fact that a sizeable percentage of U.S. voters had recently voted for Alabama Governor George Wallace in the 1964 Democratic Presidential primary elections.Wallace was among the most prominent opponents of racial desegregation and efforts to secure equal rights for African Americans in the 1960s.

In his inaugural address as Governor on January 14, 1963, he famously committed himself to “segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

On June 11, 1963, Wallace took his infamous “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” at the University of Alabama. He literally stood in front of the door of the traditionally segregated school to try to block the entry of two black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood.

That and other highly publicized anti-integration antics and statements by Wallace made him the darling of pro-segregation whites in Southern and Northern states.

Buoyed by his notoriety, Wallace ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1964 against incumbent President Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had succeeded John F. Kennedy after Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963.

Like JFK, President Johnson was supportive of the Civil Rights movement and committed to enforcing court-mandated desegregation of schools and other public facilities.

As Attorney General, Robert Kennedy was in the forefront of that battle. He was also helping Johnson push for enactment of landmark civil rights legislation in Congress, which had initially been proposed by his brother in 1963.

During the Democratic primary race, George Wallace waged a fiery populist campaign against Johnson, the Democratic and Washington establishment and desegregation.

Editorial writers, church leaders, trade unions, Democratic Party leaders and many other people and groups denounced him as an extremist, a right-wing racist and kook.

He won a third of the votes in Wisconsin, 43% in Maryland and nearly 30% in Indiana.

Robert F. Kennedy’s May 6th speech at the University of Pennsylvania came one day after the Indiana primary.

Kennedy decided to comment on it.

Here’s how the Associated Press story summarized what he said:

PHILADELPHIA (AP) – Atty. Gen. Robert F. Kennedy says he “was not surprised” at the strong vote for Gov. George C. Wallace of Alabama in the Indiana presidential primary.

Kennedy, speaking to 300 law students at the University of Pennsylvania Wednesday, said “there is a revolution now in the United States over civil rights and people don’t like to have their lives disturbed.”

“It’s not surprising then,” he added, “that one-third of the people in Indiana voted for Wallace. About one-fifth of the people are against everything all the time.”

Wallace, who campaigned against the civil rights bill pending in the Senate, got more than 29 per cent of the votes in losing to Democratic Gov. Matthew E. Welsh.

Of course, Johnson went on to win the Democratic nomination and the presidential election of 1964.

On that same election night in 1964, Robert F. Kennedy was elected U.S. Senator for New York.

Four years later, his own run at the presidency was cut short when he was assassinated by Sirhan Sirhan.

Would Kennedy have won the 1968 presidential election if he’d lived? Possibly.

Republican Richard Nixon won with less than a 1% margin in the popular vote over Democratic nominee Hubert H. Humphrey, who was less well known and less popular than Kennedy.

George Wallace ran for president again in 1968 as a third party candidate.

His policy positions appealed to independent, anti-establishment voters. The majority were angry white men.

They felt the federal government and courts were trying to force things down their throats that they totally disagreed with and the politicians were wasting their tax dollars on welfare and foreign aid. And, they agreed with Wallace’s claim that “there's not a dime's worth of difference between the two major parties.”

Wallace pledged to address many of the key things they were against. He pledged to end federal efforts at desegregation, reduce spending on welfare programs, slash foreign aid, stop the “tyranny” of the U.S. Supreme Court and block gun control proposals.

In the November 1968 election he received 13.5% of the popular vote.

As in 1964, most of the people who voted for Wallace in 1968 clearly fit the demographics of the “antis” Robert Kennedy had in mind when he made his famous observation.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on the Famous Quotations Facebook page

Related reading…