You probably know the famed “Miranda Rights” warning police are supposed to recite to someone they are arresting.

You probably know the famed “Miranda Rights” warning police are supposed to recite to someone they are arresting.

Even if you’ve never been arrested and heard it spoken by a law enforcement officer in real life, it’s spoken by characters in thousands of TV shows, movies, and books.

The exact language varies from state to state and in fictional uses, but in most cases the key lines are — or are close to — the following:

“You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you. Do you understand the rights I have just read to you?”

Since the late 1960s, those words, especially “You have the right to remain silent,” have become famous. But most people know little about their origin.

The Miranda Rights warning dates back to June 13, 1966, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision on the case Miranda v. Arizona.

That case involved a 22-year-old Arizona man named Ernesto Arturo Miranda.

Miranda had a tough life with a checkered past. By 1966, he had previously been arrested for of a number of crimes, including burglary, vagrancy, armed robbery, being a “peeping Tom,” and car theft. As a teenager, he was sentenced to time in an Arizona “reform school” twice and later spent time in jails in California, Texas, Ohio and Arizona.

In the early 1960s, Miranda was a free man who worked as a laborer at various jobs in Phoenix and generally stayed out of trouble.

Then, on March 2, 1963, an 18-year-old Phoenix woman told police a man had abducted her, driven her into the desert and raped her. Her description of the man’s truck led the police to Miranda. The victim failed to identify him in a line-up. But the police decided to take him into custody and interrogate him. After hours of questioning, Miranda signed a confession. He was soon convicted and sent to jail.

However, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) decided to appeal Miranda’s conviction, after he later claimed he was innocent and that his confession had been coerced. The ACLU focused, among other things, on the fact that Miranda had not been aware of his right under the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution not to say anything that would incriminate him. Nor had the police made him aware of that right.

Under the Fifth Amendment, “No person...shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.” That’s the part people are referring to when they “take the Fifth” and refuse to testify about something.

Miranda v. Arizona was appealed up to the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices ultimately ruled that Miranda’s rights had indeed been violated. The court’s decision included a section that became the basis for what was soon being called “Miranda Rights.”

Miranda v. Arizona was appealed up to the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices ultimately ruled that Miranda’s rights had indeed been violated. The court’s decision included a section that became the basis for what was soon being called “Miranda Rights.”

The relevant text from the court decision says:

“Prior to any questioning, the person must be warned that he has a right to remain silent, that any statement he does make may be used as evidence against him, and that he has a right to the presence of an attorney, either retained or appointed. The defendant may waive effectuation of these rights, provided the waiver is made voluntarily, knowingly and intelligently. If, however, he indicates in any manner and at any stage of the [384 U.S. 436, 445] process that he wishes to consult with an attorney before speaking there can be no questioning. Likewise, if the individual is alone and indicates in any manner that he does not wish to be interrogated, the police may not question him. The mere fact that he may have answered some questions or volunteered some statements on his own does not deprive him of the right to refrain from answering any further inquiries until he has consulted with an attorney and thereafter consents to be questioned.”

This was boiled down to the lines in the standard Miranda Rights warning spoken to suspects by law enforcement officers. The required wording varies slightly from state to state, but always embodies the basic thrust of the Supreme Court decision.

Unfortunately for Ernesto Miranda, the Supreme Court’s ruling didn’t end his long string of bad luck.

It overturned his initial conviction and set a major legal precedent, but it didn’t actually exonerate him.

The State of Arizona decided to retry Miranda on the rape charge. In the second trial, his confession was not used, but his estranged common law wife testified against him. On March 27, 1967, he was convicted again and sent back to prison.

Although Miranda received a harsh sentence of 20 to 30 years, he was paroled in 1972. Over the next few years, he was arrested several times for mostly minor offences, but he stayed out of serious trouble and became something of a celebrity.

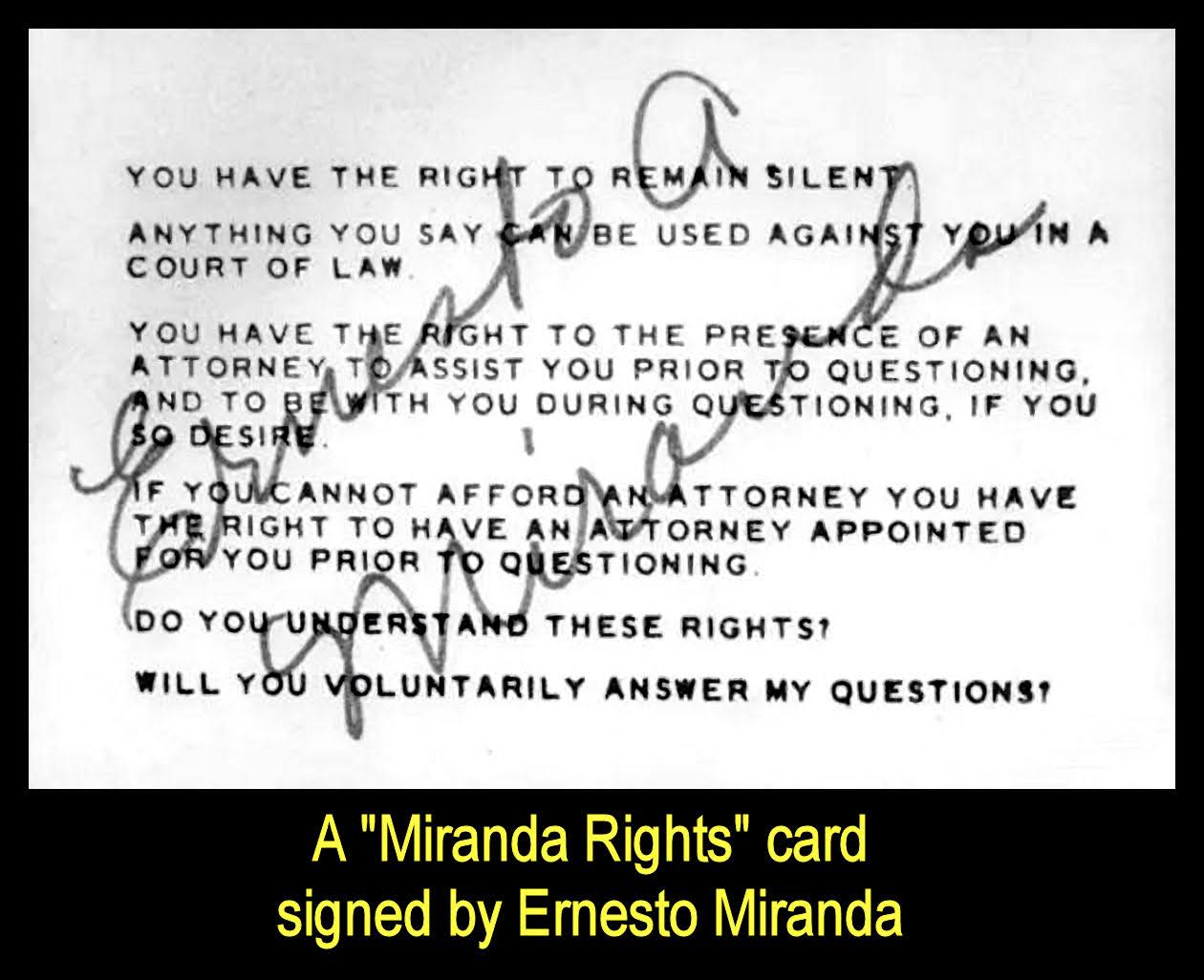

One of the ways he made money in his final years was by selling autographed “Miranda Rights cards” showing the language of the required warning his Supreme Court case had embedded into American law and our language.

In January 1976, Miranda was stabbed to death in the men’s room of a bar in Phoenix, after a dispute over a poker game. A 23-year-old Mexican man who had been there was initially held for the slaying. However, he was not charged due to a lack of evidence and headed back to Mexico.

Among the things found in Ernesto Miranda’s pockets after his death were several autographed Miranda Rights cards.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Another quote linked to June 13 is the famed quip by Baseball Hall of Famer Satchel Paige, “Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you.” You can read the background on that quotation in my post at this link.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Questions? Email me or post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page.

Related reading, listening and stuff…