On December 29, 1890, U.S. Seventh Cavalry troopers gunned down more than 200 Lakota Indians — including men, women and children — at Wounded Knee Creek on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

The Army initially called it “The Battle of Wounded Knee.”

In truth, it wasn’t a battle.

Today, it’s generally called what it really was — the Wounded Knee Massacre.

The famous quote that’s now associated with this tragic event is “Bury my heart at Wounded Knee.”

But those words were not originally written with the infamous massacre in mind.

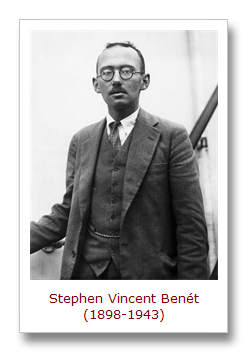

They come from the poem “American Names,” written by American poet Stephen Vincent Benét and first published in the October 1927 issue of the Yale Review.

Benét’s poem is a patriotic ode expressing his love for American place names.As he explained in the first verse:

“I have fallen in love with American names,The sharp names that never get fat,

The snakeskin-titles of mining-claims,

The plumed war-bonnet of Medicine Hat,

Tucson and Deadwood and Lost Mule Flat.”

Books of quotations often include this first verse from “American Names” and the final verse, which contains the famous line about Wounded Knee.

They usually omit the fourth verse, which blithely drops the N-word:

“I will fall in love with a Salem tree

And a rawhide quirt from Santa Cruz,

I will get me a bottle of Boston sea

And a blue-gum nigger to sing me blues.

I am tired of loving a foreign muse.”

Benét’s seemingly nostalgic use of the old racial slur “blue-gum nigger” and other lines in the poem indicate that he was enamored with the romantic sound of many American place names and was oblivious to (or didn't care about) any potential negative connotations they might have.

The poem’s mention of Wounded Knee is simply as one of those good old American place names, which Benét deems superior to “foreign” names.In the last verse he suggests that the spirits of American soldiers killed in Europe during the First World War could not find peace in their burial grounds over there.

Speaking in the voice of a dead American soldier, Benét ended the poem with these lines:

“I shall not rest quiet in Montparnasse.I shall not lie easy at Winchelsea.

You may bury my body in Sussex grass,

You may bury my tongue at Champmedy.

I shall not be there. I shall rise and pass.

Bury my heart at Wounded Knee.”

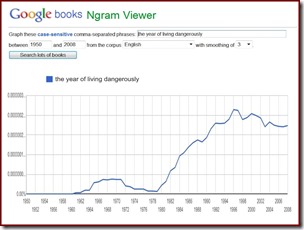

It was long after the publication of “American Names” that its final line became associated with the Wounded Knee massacre.

That literary connection was made in 1970, when American historian and novelist Dee Brown used Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee as the title of a groundbreaking book that tells the history of the American West from the Indians’ perspective.

After the publication of Brown’s book, the phrase “Bury my heart at Wounded Knee” became forever linked to the massacre that took place at Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890.

After the publication of Brown’s book, the phrase “Bury my heart at Wounded Knee” became forever linked to the massacre that took place at Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890. It has also been used to poetically encapsulate a broader sense of loss, sadness and outrage over the historic mistreatment Indians in North America.

Perhaps the most poignant use was by the great Canadian Cree singer-songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie.

In 1990, she wrote a song titled “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” which comments on the continuing abuse of Indians and Indian rights by governments and big corporations.

The chorus goes:

“Bury my heart at Wounded Knee

Deep in the earth

Cover me with pretty lies

Bury my heart at Wounded Knee.”

You can read the full lyrics of Buffy’s deeply emotional song here and see a video of her performing it live by clicking this link or the photo of her at right.

“Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” was originally on her album Coincidence and Likely Stories (1992) and is also included on her compilation album Up Where We Belong (1996).

I think it’s one of the greatest protest songs ever written, by one of the greatest of the many great singer/songwriters who started out in the 1960s folk music scene.

I understand that Stephen Vincent Benét is considered to be a great poet and that many people like his poem “American Names.”

Personally, I am moved far more by Buffy Sainte-Marie’s song “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” and by Dee Brown’s book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.

If you listen to that song and read that book, or watch the HBO adaptation of the book, you will have a better understanding why some people view Benét’s gushingly patriotic poem as “pretty lies.”

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Questions? Email me or post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page.

Related reading, viewing and listening…

It comes at the end of the next to last verse:

It comes at the end of the next to last verse:

However, although Aïssé did write something like that, the attributed quote is a case of something gained in translation.

However, although Aïssé did write something like that, the attributed quote is a case of something gained in translation.