The word almighty, used in connection with God, appears 57 times in the King James Version of the Bible.

Starting in the Book of Genesis, God is variously referred to as “the Almighty God,” “God Almighty” and, most often, simply as “the Almighty.”

The English idiom “the almighty dollar,” which is commonly used to mock the worship of wealth and money, does not come from the Bible.

It was coined in 1836 by the American author Washington Irving, whose best known works include the short stories “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle.”

There is an earlier, similar term. In 1616, the English playwright and poet Ben Jonson used the term “almighty gold” in his poem “Epistle to Elizabeth, Countess of Rutland.”

But the more familiar “almighty dollar” first appeared in a travel story Irving wrote about a steamboat trip he took through the Louisiana bayous.

The story, titled “The Creole Village,” was originally published in the November 12, 1836 issue of Knickerbocker Magazine.

Irving was impressed by the laid back lifestyle of the Creole people who lived in Louisiana’s bayou country and by how unconcerned they seemed (at least to him) about making or having money.

He wrote in his travel piece:“The inhabitants, moreover, have none of that eagerness for gain and rage for improvement which keep our people continually on the move...In a word, the almighty dollar, that great object of universal devotion throughout our land, seems to have no genuine devotees in these peculiar villages; and unless some of its missionaries penetrate there, and erect banking houses and other pious shrines, there is no knowing how long the inhabitants may remain in their present state of contented poverty.”

Near the end of the piece, Irving opined:

“As we swept away from the shore, I cast back a wistful eye upon the moss-grown roofs and ancient elms of the village, and prayed that the inhabitants might long retain their happy ignorance, their absence of all enterprise and improvement, their respect for the fiddle, and their contempt for the almighty dollar.”

I suspect this romantic vision overestimated how content the locals were to be poor.

Of course, in 1855, when “The Creole Village” was included in a collection of his stories called Wolfert’s Roost, Irving made it clear that he had meant no offense — to the almighty dollar, that is.

In a satirical footnote in that book (later included in larger Irving anthologies like The Crayon Miscellany), Irving wrote:

“This phrase [the almighty dollar], used for the first time in this sketch, has since passed into current circulation, and by some has been questioned as savoring of irreverence. The author, therefore, owes it to his orthodoxy to declare that no irreverence was intended even to the dollar itself; which he is aware is daily becoming more and more an object of worship.”

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Email me or Post them on the Famous Quotations Facebook page.

RELATED READING AND LISTENING (Click on an image to see that item on Amazon)

As

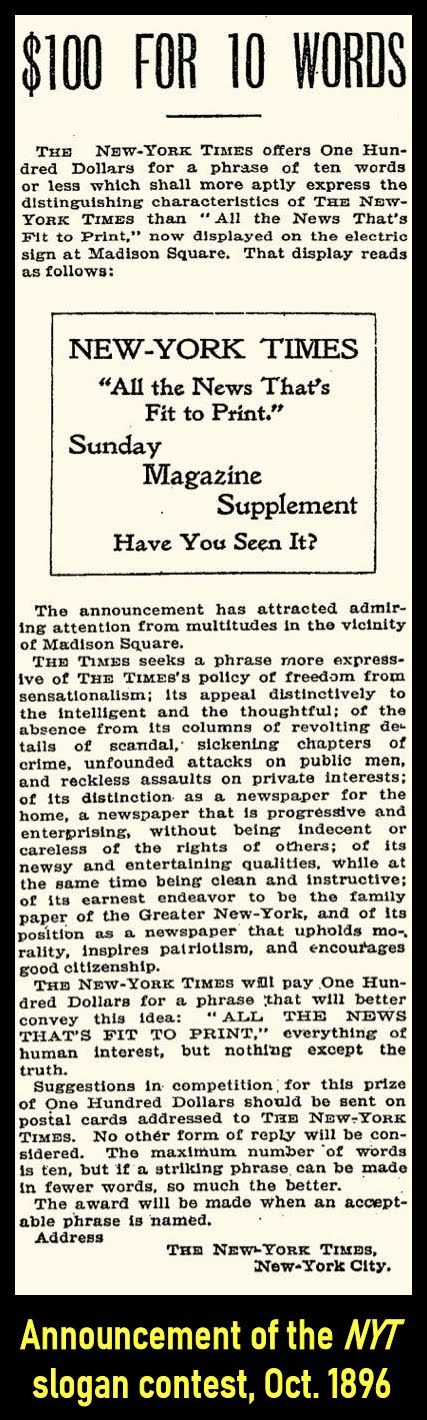

As  Some of the slogan entries emphasized the idea that The New York Times didn’t print the type of lurid stories found in many other newspapers, such as:

Some of the slogan entries emphasized the idea that The New York Times didn’t print the type of lurid stories found in many other newspapers, such as: