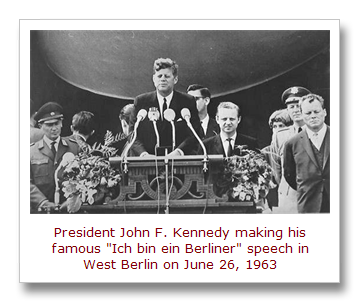

One of the famous quotations linked to the date June 26th is a line President John F. Kennedy spoke in German on June 26, 1963: “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

Kennedy used the line twice that day in a historic speech in West Berlin, which was then separated from Communist-controlled East Berlin by the Berlin Wall.

His intention was to express his solidarity with the people there, by symbolically calling himself a citizen of Berlin. And, the literal translation of “Ich bin ein Berliner” is indeed “I am a Berliner.”

However, there’s been a long-running debate over Kennedy’s grammar.

His use of “ein” is the issue.

“Ein” does means “a” in English. But Germans use the word “Berliner” without “ein” to mean “a citizen of Berlin.”

They say “Ich bin Berliner” when they want to say the English equivalent of “I am a Berliner.”

The term “ein Berliner” — when used as a noun — refers to the jelly-filled, doughnut-like pastry Germans call “ein Pfannkuchen Berliner” or “ein Berliner” for short.

Similarly, a citizen of Frankfurt, Germany, would say “Ich bin Frankfurter,” rather than “Ich bin ein Frankfurter.” The latter could theoretically be interpreted to mean “I am a hot dog.”

For this reason, Kennedy’s line “Ich bin ein Berliner” has generated both amusement and heated discussion over the years.

Technically, it’s true that what he said in German could be interpreted as “I am a jelly-filled doughnut.”

That’s why some people claim the quote is laughable.

It has also been claimed that West Germans who were there listening to Kennedy laughed at him when he said the line.

On the flip side, some people have claimed “ein Berliner” is grammatically correct when used by someone who is not really a citizen of Berlin. They say the doughnut theory is an urban legend.

My own view is that Kennedy’s grammar was non-standard.

However, much more importantly, the people of West Berlin knew exactly what Kennedy meant when he said “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

They knew he wasn’t talking about a jelly-filled doughnut. And, they found his words inspiring, not laughable.

You can see why by reading or watching a video of Kennedy’s speech.

It’s one of the most famous speeches in history. And, the crowd of more than 120,000 West Germans who were there on June 26, 1963 were cheering loudly — not laughing.

* * * * * * * * * *

John F. Kennedy’s “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech

Delivered in front of the Berlin Wall at Rudolph Wilde Platz in West Berlin

June 26, 1963

I am proud to come to this city as the guest of your distinguished Mayor, who has symbolized throughout the world the fighting spirit of West Berlin. And I am proud to visit the Federal Republic with your distinguished Chancellor who for so many years has committed Germany to democracy and freedom and progress, and to come here in the company of my fellow American, General Clay, who has been in this city during its great moments of crisis and will come again if ever needed.

Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was “Civis Romanus sum.” [“I am a Roman Citizen”] Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was “Civis Romanus sum.” [“I am a Roman Citizen”] Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is “Ich bin ein Berliner.” I appreciate my interpreter translating my German.

There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the Communist world. Let them come to Berlin.

There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin.

And there are some who say, in Europe and elsewhere, we can work with the Communists. Let them come to Berlin.

And there are even a few who say that it is true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Lass’ sie nach Berlin kommen. Let them come to Berlin.

Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect. But we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in — to prevent them from leaving us. I want to say on behalf of my countrymen who live many miles away on the other side of the Atlantic, who are far distant from you, that they take the greatest pride, that they have been able to share with you, even from a distance, the story of the last 18 years. I know of no town, no city, that has been besieged for 18 years that still lives with the vitality and the force, and the hope, and the determination of the city of West Berlin.

While the wall is the most obvious and vivid demonstration of the failures of the Communist system — for all the world to see — we take no satisfaction in it; for it is, as your Mayor has said, an offense not only against history but an offense against humanity, separating families, dividing husbands and wives and brothers and sisters, and dividing a people who wish to be joined together.

What is true of this city is true of Germany: Real, lasting peace in Europe can never be assured as long as one German out of four is denied the elementary right of free men, and that is to make a free choice. In 18 years of peace and good faith, this generation of Germans has earned the right to be free, including the right to unite their families and their nation in lasting peace, with good will to all people.

You live in a defended island of freedom, but your life is part of the main. So let me ask you, as I close, to lift your eyes beyond the dangers of today, to the hopes of tomorrow, beyond the freedom merely of this city of Berlin, or your country of Germany, to the advance of freedom everywhere, beyond the wall to the day of peace with justice, beyond yourselves and ourselves to all mankind.

Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, all are not free. When all are free, then we can look forward to that day when this city will be joined as one and this country and this great Continent of Europe in a peaceful and hopeful globe. When that day finally comes, as it will, the people of West Berlin can take sober satisfaction in the fact that they were in the front lines for almost two decades.

All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin.

And, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Questions? Email me or post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page.

Related reading, listening and stuff…

noticed a headline for an Associated Press story about North Korea that was interesting from a word and quotation history perspective. It said:

noticed a headline for an Associated Press story about North Korea that was interesting from a word and quotation history perspective. It said:

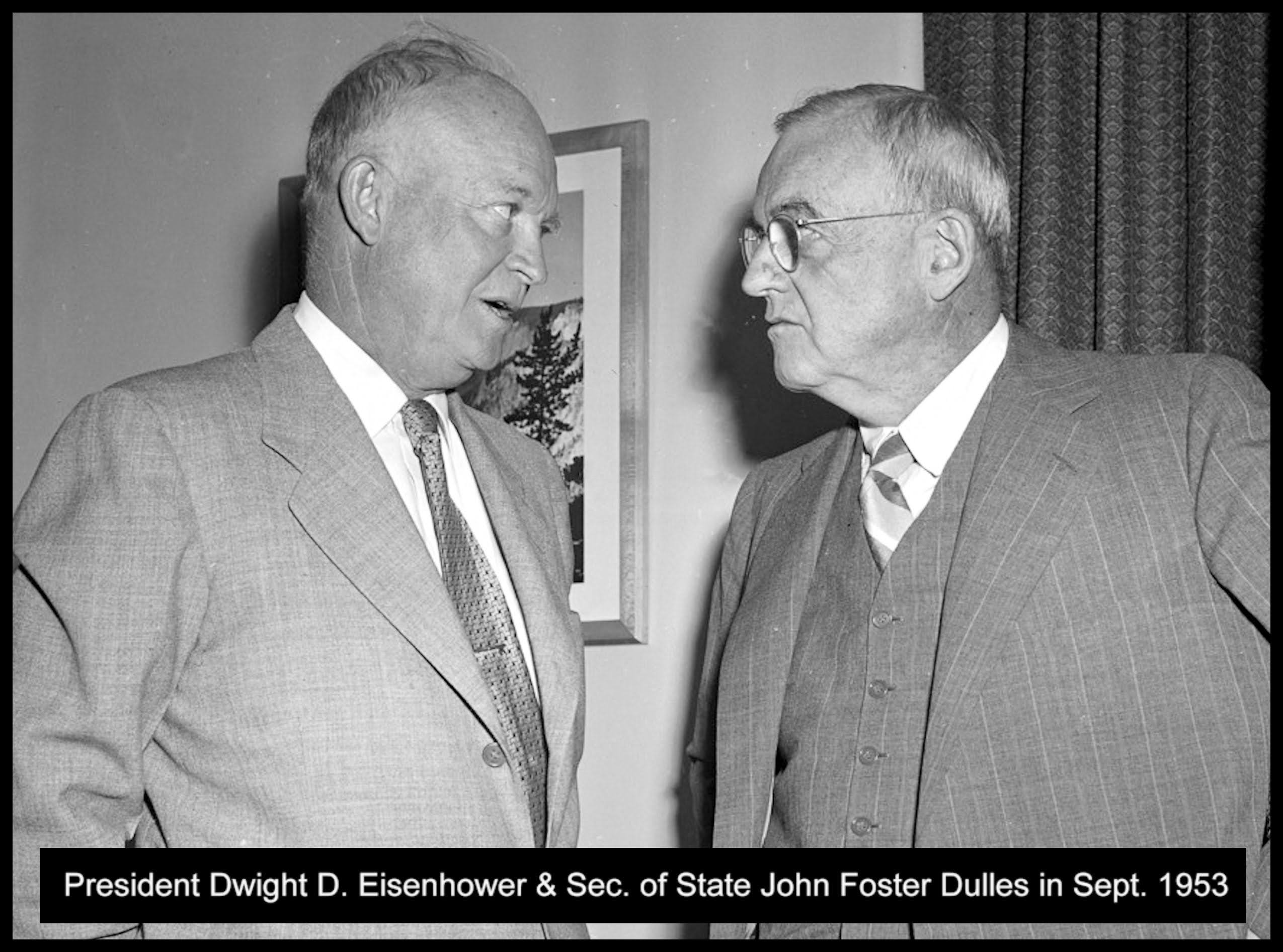

The article is titled “HOW DULLES AVERTED WAR.” (Ironically, the cover of that issue features a photograph of actress

The article is titled “HOW DULLES AVERTED WAR.” (Ironically, the cover of that issue features a photograph of actress