When Columbia Records released the first, self-titled album

But Columbia music producer John Hammond, who signed Dylan to the label, had faith in the young folk singer.

He ignored the jibes of other music executives who dubbed Dylan “Hammond’s Folly” and, in eight sessions strung out over the next twelve months, he recorded a second album with Dylan for Columbia.

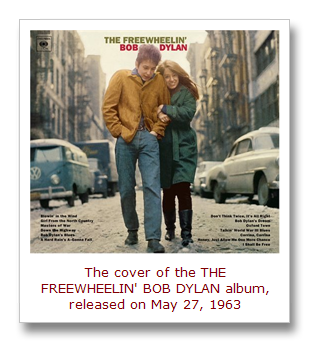

That album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, was released on May 27, 1963, three days after Dylan’s 22nd birthday.

It’s now considered one of the greatest and most influential albums in American music history.

The Freewheelin’ LP includes what remain some of Dylan’s best-known songs, such as “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Girl from the North Country,” “Masters of War,” “Don't Think Twice, It’s All Right” and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

“Blowin’ In The Wind” became the most famous song from the album. But the one that stuck in my mind even more when I first listened to the album in 1963 was “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

The song’s foreboding title, from a phrase in the chorus, was memorable in itself and has since been widely cited and repurposed.

I believe it struck a special chord with kids from the Baby Boom generation, like me.

We grew up at a time when a nuclear war between the US and the USSR seemed inevitable.

In elementary school, we practiced “duck and cover” drills and watched public service films like the one at right, in which a narrator and “Bert the Turtle” helpfully explain what to do when the A-bombs start falling.

Bert told us: “The flash of an atomic bomb can come at any time, no matter where you may be...When there is a flash, duck and cover, and do it fast!”

It seems a bit humorous now. But back then, during the height of the Cold War years, the possibility of an atomic Armageddon was a serious and constant fear.

Movies, TV shows, books, magazine stories and politically-oriented songs of the era helped stoke that fear by portraying what a nuclear holocaust and the hellish aftermath would be like.

That frightening scenario is also conjured up by “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

Hentoff said the song “was written during the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962 when those who allowed themselves to think of the impossible results of the Kennedy-Khrushchev confrontation were chilled by the imminence of oblivion.”

Dylan is then quoted as saying: “Every line in it is actually the start of a whole song. But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this one.”

Fortunately, Bob and the world survived. On May 24, 2014, he turned 73.

I’m not many years from that age myself.

Today, I can listen to “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” from a less paranoid perspective. But it still gives me the chills.

In case you haven’t read the lyrics, I’m reprinting them below.

By clicking this link or image at left, you can see Dylan perform the song in 1964, in an episode of the Canadian TV show Quest.

And, by clicking this link, you can listen to some of the many interesting cover versions that have been recorded by other musicians and groups over the years.

Here’s to you, Bob. Hope you had a good birthday! Glad you’ve been wrong about that hard rain … so far.

“A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall” by Bob Dylan

(Copyright © 1963 by Warner Bros. Inc.; renewed 1991 by Special Rider Music)

Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, where have you been, my darling young one?

I’ve stumbled on the side of twelve misty mountains

I’ve walked and I’ve crawled on six crooked highways

I’ve stepped in the middle of seven sad forests

I’ve been out in front of a dozen dead oceans

I’ve been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard

And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, and it’s a hard

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

Oh, what did you see, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, what did you see, my darling young one?

I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it

I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it

I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’

I saw a room full of men with their hammers a-bleedin’

I saw a white ladder all covered with water

I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken

I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children

And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

And what did you hear, my blue-eyed son?

And what did you hear, my darling young one?

I heard the sound of a thunder, it roared out a warnin’

Heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world

Heard one hundred drummers whose hands were a-blazin’

Heard ten thousand whisperin’ and nobody listenin’

Heard one person starve, I heard many people laughin’

Heard the song of a poet who died in the gutter

Heard the sound of a clown who cried in the alley

And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

Oh, who did you meet, my blue-eyed son?

Who did you meet, my darling young one?

I met a young child beside a dead pony

I met a white man who walked a black dog

I met a young woman whose body was burning

I met a young girl, she gave me a rainbow

I met one man who was wounded in love

I met another man who was wounded with hatred

And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

Oh, what’ll you do now, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, what’ll you do now, my darling young one?

I’m a-goin’ back out ’fore the rain starts a-fallin’

I’ll walk to the depths of the deepest black forest

Where the people are many and their hands are all empty

Where the pellets of poison are flooding their waters

Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison

Where the executioner’s face is always well hidden

Where hunger is ugly, where souls are forgotten

Where black is the color, where none is the number

And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it

And reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it

Then I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’

But I’ll know my song well before I start singin’

And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page or send me an email.

Related listening and reading…