It’s impossible to predict what quotes will come to be indelibly associated with each president of the United States. However, the famous quotes most presidents are remembered for include some they may regret and be haunted by later.

One of the quotes by George Herbert Walker Bush in that category is his remark about “the vision thing.”

In January 1987, Bush was near the end of his second term as Vice President under Ronald Reagan. It was common knowledge that he planned to run for President in 1988.

However, some critics — including some in Bush’s own Republican Party — viewed Bush as a politician who lacked the ability to clearly articulate his fundamental beliefs and policies, as Reagan did so well.

The January 26, 1987 issue of Time magazine included an article by journalist Robert Ajemian exploring this topic. It was titled “Where Is the Real George Bush?”

One of the anecdotes in that story made “the vision thing” a famous/infamous quotation.

“Colleagues say that while Bush understands thoroughly the complexities of issues, he does not easily fit them into larger themes,” Ajemian wrote. “This has led to the charge that he lacks vision. It rankles him. Recently he asked a friend to help him identify some cutting issues for next year’s campaign. Instead, the friend suggested that Bush go alone to Camp David for a few days to figure out where he wanted to take the country. ‘Oh,’ said Bush in clear exasperation, ‘the vision thing.’ The friend’s advice did not impress him.”

Bush’s comment about “the vision thing” was quickly picked by the press and political commentators and used against him by his critics.

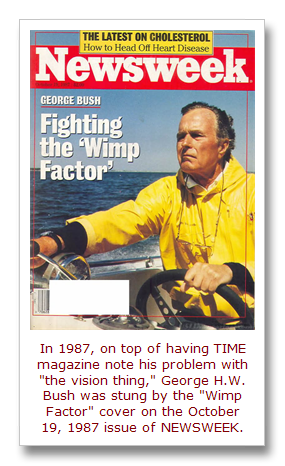

Bush defeated Democrat Michael Dukakis in the November 1988 presidential election. And, he won despite allegations of his “vision problems” and other indignities, such as the October 19, 1987 issue of Newsweek that featured a cover headline essentially calling him a “wimp” (“GEORGE BUSH: FIGHTING THE ‘WIMP FACTOR’”).

However, Bush’s lack of “the vision thing” as president, especially in terms of domestic policies, was seen as a factor in his defeat by Democrat Bill Clinton in the 1992 presidential race. And, today, the vision quote is still commonly cited in bios of Bush. For example, even the Bush bio posted on the official U.S. Senate website says:

As noted by a brief entry in Wikipedia, “the vision thing” went on to become a metonym, i.e., a shorthand figure of speech. It is now used as a description “for any politician’s failure to incorporate a greater vision in a campaign, and has often been applied in the media to other politicians or public figures.”“Bush...suffered from his lack of what he called ‘the vision thing,’ a clarity of ideas and principles that could shape public opinion and influence Congress. ‘He does not say why he wants to be there,’ complained columnist George Will, ‘so the public does not know why it should care if he gets his way.’”

Ironically, January 26th also happens to be the anniversary of two quotes that Bill and Hillary Clinton later regretted. For more about those quotes, click this link...

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on the Famous Quotations Facebook group.

Further reading: books about presidential quotations…