On August 8, 1966, Capitol Records released the Beatles album Revolver in the United States. (In the UK, the LP was released by Parlophone on August 5.)

Revolver became an immediate chart-topper and is now widely considered to be one of the greatest albums in music history.

It includes several especially famous and popular Beatle songs, like “Eleanor Rigby,” “Yellow Submarine,” and “Here, There and Everywhere.”

Moreover, as a whole, Revolver was a watershed album for the Beatles and popular music — lyrically, musically and even technologically. (Some songs include recording effects never or rarely heard before on a mainstream pop album, like automatic double tracking, tape looping and flanging.)

Rock music historian and critic Richie Unterberger called it “one of the very first psychedelic LPs.”

One of the trippiest songs on the album is “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

Written primarily by John Lennon, it is clearly an ode to the hallucinogenic drug LSD. (In 1972, Lennon openly referred to it as “my first psychedelic song.”)

Unlike some other songs on Revolver, few people can recall many of the lyrics from “Tomorrow Never Knows.” If you look for them on the Internet or in books, you’ll find several variations. Almost none have all the lyrics right. But the famous first line — “Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream” — is well known, cited by thousands of websites and books and usually quoted correctly.

A year or more before they recorded Revolver, John and the other Beatles — Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr — began experimenting with “acid,” like many other musicians who were on the cutting edge of rock music and pop culture in the mid-1960s.

As recounted in many books about the Beatles and psychedelic drugs, John got the opening words of the song from a guide for users of hallucinogens that was co-authored by the Acid King himself, Timothy Leary, with his fellow psychoactive drug pioneers Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert (a.k.a. Ram Dass).

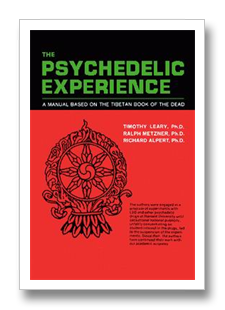

Titled The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, it was published in 1964, a couple of years before Leary began using his catchphrase “Turn on, tune in, drop out.”

In the introduction of the “manual,” Leary, Metzner and Alpert gave this advice to newbie LSD trippers who might feel a bit anxious when they saw the walls melting or felt like they were dying:

“Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream.”

They adapted that recommendation from a line in The Tibetan Book of the Dead, an 8th century Buddhist text originally said to be a guide for people who actually were in the process of dying, prior to reincarnation.

That venerable book says that one stage in the process involves scary hallucinations, or “hell-visions.”

According to the translation in The Psychedelic Experience, the Book of the Dead helpfully explains:

“The teaching concerning the hell-visions is the same as before; recognize them to be your own thought-forms, relax, float downstream.”

I can’t vouch for the translation or for how well this advice may work during the process of dying.

However, not long after the album Revolver was released, back in my Hippie days, I did do my own experimenting with LSD. And, in that context, I can say that the suggestion to relax and float downstream was pretty good advice.

In addition, having listened to “Tomorrow Never Knows” a thousand times or so, I can say that I’m pretty sure the correct lyrics are as follows (although, given the distortion effect used on Lennon’s voice, I can understand why there are several versions floating around):

“Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream,It is not dying, it is not dying.

Lay down all thought, surrender to the void,

Lay down all thought, surrender to the void, It is shining, it is shining.

That you may see the meaning of within,

It is being, it is being.

That love is all and love is everyone,

It is knowing, it is knowing.

That ignorance and hate may mourn the dead,

It is believing, it is believing.

But listen to the color of your dream,

It is not living, it is not living.

Or play the game ‘Existence’ to the end,

Of the beginning, of the beginning.”

By the way, the title of the song has nothing to do with drugs or death or Tibetan Buddhism. Like “A Hard Day’s Night” it’s another Beatles song title that started out as a Ringo Starr malapropism.

During a 1964 interview, Ringo answered a question by saying “Tomorrow never knows.”

Lennon remembered the quip and later explained that he used it as the song’s title “to sort of take the edge off the heavy philosophical lyrics.”

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Questions? Email me or post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page.

Related listening and reading…