February 24, 2022

February 21, 2022

“Workers of the World, Unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains!”

You can find many different lists of “books that changed the world” on the Internet.

Those lists vary considerably. But there are some books that show up on almost all of them.

One is The Manifesto of the Communist Party, more commonly known as The Communist Manifesto.

The Manifesto was co-written by Karl Marx and his friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels.

According to most sources, it was first published in London on February 21, 1848 and it did indeed change the world by serving as a key philosophical foundation for socialism and communism. (Some sources give the date as February 26, 1848, but I think they’re wrong.)

The original edition of this seminal work by Marx and Engels was published in German, their native language.

Over the next few years it was translated into many other languages, including English. Several famous quotations from The Communist Manifesto are included in many books of quotations and still frequently cited today.

One is the opening sentence of the Preamble:

“A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of Communism.”

Another is the first line of Chapter I:

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

The other famous words in The Communist Manifesto are its closing lines, at the end of Chapter IV.

The official English translation of the last four sentences, as approved by Engels, are:

“Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working Men of All Countries, Unite!.”

The shortened, more familiar — and often parodied — mistranslation of the last few sentences is:

“Workers of the World, Unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains!”

As it turned out, other people’s visions of “Communistic revolution” and Marxism weren’t exactly what Marx and Engels had in mind.

In a letter he wrote on August 5, 1890, Engels remarked: “Just as Marx used to say, commenting on the French ‘Marxists’ of the late [18]70s: ‘All I know is that I am not a Marxist.’”

You can read some humorous take-offs on the “Workers of the world” quote in the post on my Quote/Counterquote blog at this link.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Questions? Email me or post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page.

Related reading and listening…

February 12, 2022

“All the news that’s fit to print.”

The edition printed on that date was the first to have the slogan printed at the top left corner of the front page.

It has continued to appear there ever since on print copies of the NYT. (It’s not shown on the digital version.)

Previously, the top left corner of the first page had been used to note the number of pages in that day’s edition.

Contrary to what you may read in some books or internet posts, the use on February 10, 1897 was not the first appearance of the slogan.

It was initially launched in October 1896, a few months after Adolph Ochs became the publisher.

The paper had been struggling and nearly went bankrupt before Ochs took over.

He wanted to elevate the quality of its reporting and distinguish it from the “yellow journalism” newspapers that were common at the time. Such papers were filled with stories that tended to be lurid, sensationalized and often factually inaccurate or outright false.

To sum up his vision for The Times, Ochs coined the slogan “All the news that’s fit to print.”

It debuted publicly on a sign he had placed above New York’s Madison Square in October 1896. The sign spelled out the slogan in red lights.

Later in October, he had it printed at the top of The Times’ editorial page and used it in ads published in newspaper trade journals.

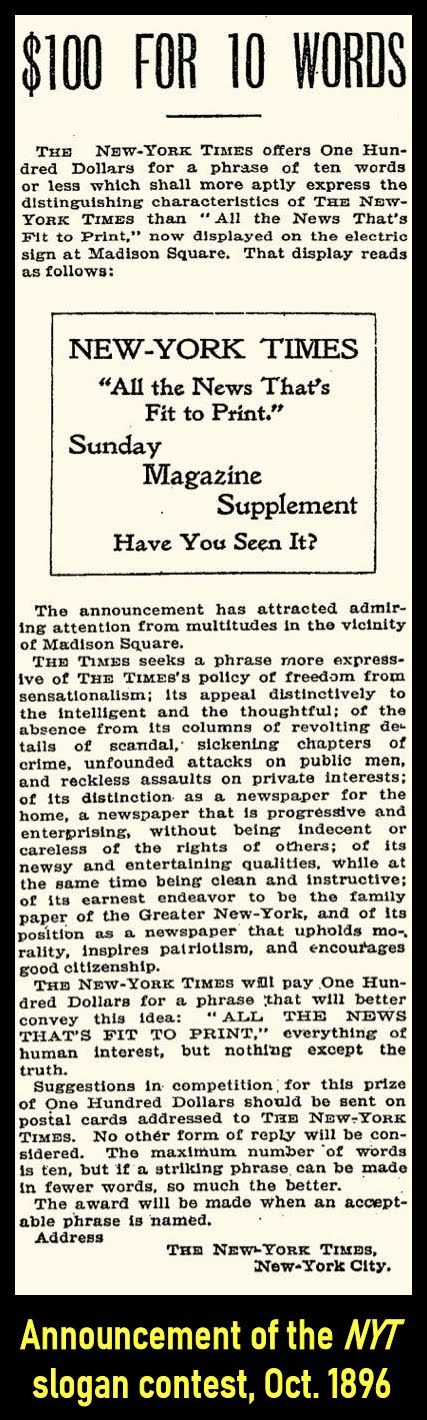

That same month, Ochs came up with what turned out to be a genius idea for publicizing the slogan and The Times. He announced a contest offering a $100 prize to anyone who could come up with a better slogan.

In 2017, NYT writer David W. Dunlap said in an article about the contest:

“Adolph S. Ochs had recently purchased the failing New York Times at what amounted to a fire sale. On the billboard and elsewhere, he tried to distinguish The Times from its competitors by stressing its gravity, thoroughness, accuracy and decorum. But he was a showman, too. He knew that a reward of $100 for a new motto would generate far more than $100 worth of publicity. He invited readers to coin ‘a phrase of 10 words or less which shall more aptly express the distinguishing characteristics of The New York Times.’ He probably had no idea what a sensation his contest would cause. Hundreds of responses began arriving at The Times’s headquarters on Park Row, near City Hall, in Lower Manhattan. Then thousands.”

The publicity created by the contest dramatically increased awareness of The Times, Ochs’ goal of making it a more trustworthy news source — and its readership. But it didn’t lead to a what Ochs considered a better slogan.

“Fresh Facts Free From Filth.”

“News, Not Nausea,”

“You Don’t Have to Apologize for Reading It.”

“It’s Safe to Read The Times.”

“We Propose to Demonstrate That Journalism Is a Decent Profession.”

“For Patriot — Simple, Good and Great; Not for the Degenerate.”

“Clean News for Clean People.”

“A Decent Newspaper for Decent People.”

“Nothing Indecent, Nothing Inane.”

“Clean as New Fallen Snow, It Covers the Whole Ground.”

“Cleanliness Is Honesty! Give Me a Bathtub and The New York Times.”

“All the News Compiled in Language Undefiled.”

Some seem to be versions inspired by Adolph Och’s motto, like:

“All News When Fit, When Not We Wait a Bit.”

“The News That Isn’t Here Is Not Worth Knowing.”

“You Do Not Want What The New York Times Does Not Print.”

“What We Do Not Publish ‘Tis Better Not to Know.”

“What It Doesn’t Print, You Don’t Care to Read.”

“Our News Is News As Is News.”

“All the News to Instruct and Amuse.”

“Such News and Views as Reason Would Choose.”

“The World’s News That’s Fit to Peruse.”

Some clever entries were acrostics, in which the first letters of each word spelled out “The Times” or “Times.” They included:

“Treats Honestly Every Topic Interesting Men Except Scandals.”

“The Information Mankind Earnestly Seeks.”

“Truthful, Instructive, Moderate, Educational, Successful.”

“Terse, Interesting, Moral, Entertaining, Sure.”

“Truthfulness, Independence, Modesty, Energy, Science.”

A few slogan entries seem ironic in retrospect, given evolution of “The Gray Lady” into a liberal-leaning newspaper. For example:

“Courageous, Conscientious, Conservative.”

“Truth Without Trumpery.”

Ochs and his staff selected what they thought were the 150 best slogan suggestions. Then Ochs asked Richard Watson Gilder, editor of The Century Magazine and one of America’s most prominent literary figures, to decide the winner.

Gilder chose the slogan “All the World’s News, but Not a School for Scandal,” submitted by D. M. Redfield of New Haven, Connecticut.

Apparently, Ochs was not impressed. He paid Redfield the $100, but decided to stick with “All the news that’s fit to print.” It became the best known newspaper slogan of all time.

Of course, back in the 1970s, avid readers of Rolling Stone, like me, were more familiar with the slogan that magazine adopted in 1969 — “All the News That Fits.”

Did we know it was a humorous variation on the NYT motto? I don’t remember. Hey, it was the ‘70s.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page or send me an email.

Related reading…

January 20, 2022

Origins of the term “brinkmanship” (aka “brinksmanship”)...

I recently

“North Korean missile tests signal return to brinkmanship.”

The term brinkmanship was coined in 1956 during the height of the Cold War, when the U.S. was facing a potential nuclear war with two other Communist powers, the Soviet Union and Red China.

It’s often spelled as brinksmanship, with an s. That spelling reflects previous terms it was based on, such as the very old word sportsmanship and more recent word gamesmanship.

The latter was popularized in the late 1940s and early 1950s by British author Stephen Potter’s humorous, best-selling book The Theory and Practice of Gamesmanship: Or the Art of Winning Games Without Actually Cheating.

Potter didn’t coin the word gamesmanship. It was first recorded in Ian Coster’s autobiographical book Friends in Aspic, published in 1939.

Coster said he heard his friend Francis Meynell use it to describe sports behavior that involved “the art of winning games by cunning against opponents with superior skill.”

However, Potter’s Gamesmanship book made the term widely known and spawned other “-manship” terms.

Potter himself helped encourage that trend by writing follow-up books like Lifemanship in 1950 and One-Upmanship in 1952.

The word brinkmanship was inspired by controversy over a quotation that became both famous and infamous.

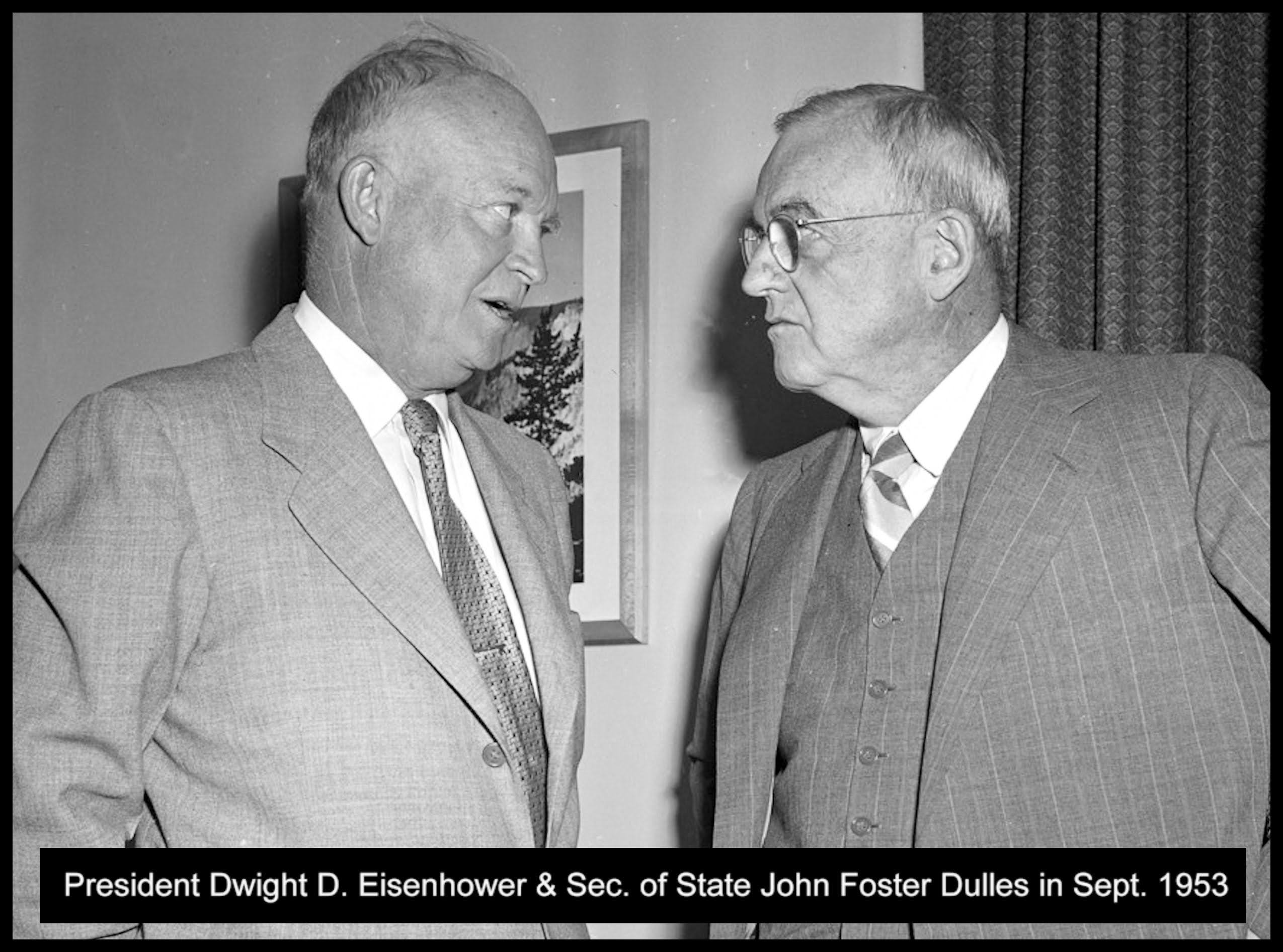

The quote appeared in an article about lawyer, politician, and statesman John Foster Dulles in the January 16, 1956 issue of Life magazine.

Since 1953, Dulles had been serving as U.S. Secretary of State under Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower. During that time, he’d dealt with a number of international political crises.

One of America’s fundamental Cold War polices was to try to prevent Communism from spreading to countries in Southeast Asia, South America and elsewhere. President Eisenhower memorably outlined that concern in a press conference on April 7, 1954.

As noted in a previous post on This Day in Quotes, Eisenhower described the threat of creeping Communism as the “falling domino principle,” soon described in the press as “the domino principle” or “the domino effect.”

Concern about the spread of Communism led to the Korean War in 1950, various other armed conflicts (eventually including the Vietnam War), and an arms race that made the risk of nuclear war a gloomy, omnipresent concern for decades.

An end to the Korean War was negotiated in 1953, the year Eisenhower became president. But during the next few years, the Eisenhower administration faced decisions about how to deal with other threats that arose through actions by the Soviet Union, Red China, and their political allies.

Those included a potential resumption of war with Red China in Korea and another potential war if Red China tried to invade Taiwan.

Eisenhower and his point man on international politics, Secretary of State Dulles, took a hard line on these and other issues involving Communist regimes.

They made it clear, publicly and through diplomatic channels, that America was willing to use what Dulles described in a speech on January 12, 1954 as “massive retaliatory power” — which clearly implied the possibility of nuclear war — to stop actions by Red China, the Soviet Union, or other actors who crossed certain political lines in the sand. (That quote by Dulles soon embedded the term “massive retaliation” into our language.)

The article about Dulles in the January 16, 1956 issue of Life discussed those and other tense situations Dulles had dealt with. It included an extensive interview with him about the tough approach he and Eisenhower took.

One of the quotes by Dulles in the article launched another new Cold War term. Speaking of the recent saber-rattling over Korea and Taiwan, he said:

“You have to take chances for peace, just as you must take chances in war. Some say that we were brought to the verge of war. Of course we were brought to the verge of war. The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is the necessary art. If you cannot master it, you inevitably get into war. If you try to run away from it, if you are scared to go to the brink, you are lost.”

That quote, with its use of the concept of going to “the brink” of atomic Armageddon as a strategy, generated considerable criticism, especially from political opponents of the Eisenhower regime.

The most notable attack came from Adlai Stevenson II. He was a prominent Democratic politician who served as Governor of Illinois and made several unsuccessful attempts to be elected President of the United States prior to his death in 1965.

In 1956, the Democratic Party tapped Stevenson as their presidential candidate to run against Eisenhower. In a speech at Hartford, Connecticut on February 25, 1956, Stevenson said:

“We hear the Secretary of State boasting of his brinkmanship—the art of bringing us to the edge of the abyss.”

That line was widely quoted in news stories and embedded the term brinkmanship into our language. Stevenson is generally credited with coining the word. It was clearly based on the then widespread use of the term gamesmanship and variations on it.

Around the same time as Stevenson’s speech, the great political cartoonist Herbert Lawrence Block, commonly known as “Herblock,” drew a cartoon that reflected his view of the brinkmanship strategy.

It shows Dulles pushing Uncle Sam toward the edge of a cliff labeled as "THE BRINK," as he says “DON’T BE AFRAID — I CAN ALWAYS PULL YOU BACK.”

If you’re interested in Cold War history, you can read a scan of the complete Life magazine issue with the article about John Foster Dulles via Google Books (here). The text is also posted in the Internet Archive (here).

As someone who was a kid in the 1950s and practiced “duck and cover” drills at school in preparation for a possible nuclear attack, I found it fascinating.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page or send me an email.

Related reading, watching & listening…

January 13, 2022

“J’Accuse!” (“I Accuse!”)

The letter was published under huge headlines that said:

J’Accuse...!

LETTRE AU PRÉSIDENT DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE.

Par ÉMILE ZOLA

In English:

I Accuse...!

LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC

By ÉMILE ZOLA

In the letter, Zola accused the French government and top military officials of anti-Semitism and of conspiring to unjustly frame, convict and imprison Alfred Dreyfus.

Dreyfus was a Jewish officer in the French Army who was convicted of treason in 1894, for allegedly passing military secrets to the Germans.

The young officer had steadfastly proclaimed he was innocent and, by 1898, clear evidence had surfaced showing he was.

The debate over Dreyfus split French society into warring cultural factions for years, in ways similar to those that have divided liberals and conservatives in America during the Trump era.

Indeed, the Dreyfus Affair involved social and political issues that would still resonate today: racial intolerance, a secret conspiracy by military and government officials, the unlawful conviction and imprisonment of an innocent man, and an example of how protests by outraged activists and revelations in the media can rock the establishment and help lead to justice and cultural changes.

However, the most widely-known legacy of the Dreyfus Affair is Zola’s quote “J’Accuse!” (usually cited without the ellipsis in the actual headline).

It is still invoked in both French and English in public attacks on injustices, lies and malfeasance committed by people in power — though few people today know much, if anything, about the events that inspired it.

The affair started when a French spy found a letter indicating that some French military officer was passing information about French artillery parts to the Germans.

The traitor was a high-ranking officer on the General Staff, Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy. But Esterhazy used phony evidence to put the blame on his subordinate, Dreyfus, who was conveniently of low rank and Jewish.

At the time, anti-Semitism was rampant among the mostly-Catholic French military leaders and public.

Dreyfus had his supporters, but the flimsy case against him was accepted by the military court and most citizens. There was some inconvenient evidence suggesting that Esterhazy was the likely traitor. However, it was generally dismissed as what would now be called “fake news.”

Dreyfus was convicted in December 1894 and sentenced to life in prison on Devil’s Island off of French Guiana. Before being sent there, he was publicly shamed and degraded in a ceremony in Paris on January 5, 1895.

The insignia was torn from his uniform. His sword was broken. He was then paraded past a crowd that shouted things like, “Death to Judas!” and “Death to the Jew.”

During 1896, as Dreyfus suffered through a hellish incarceration on Devil’s Island, a new chief of French military intelligence, Lieutenant Colonel Georges Picquart, found more evidence showing that Esterhazy was the real traitor.

Picquart’s superiors responded by sending him to a post in Tunisia and trying to keep the information he uncovered secret.

Despite the evidence, he found not guilty. This added to the outrage of Dreyfus supporters, which included Émile Zola and many of France’s other leading intellectuals and liberal activists, such as Georges Clemenceau, a long-serving member of the French National Assembly and publisher of the L’Aurore newspaper.

Zola expressed his own outrage in his “J’Accuse...!” letter. In it, he reviewed the facts surrounding the Dreyfus Affair and pointedly named specific military and public officials who were complicit in railroading Dreyfus and letting Esterhazy skate.

Zola used his quickly-famous headline words in front of a series of sentences near the end of the letter, writing:

“Mr. President…

I accuse Major Du Paty de Clam as the diabolic workman of the miscarriage of justice, without knowing, I have wanted to believe it, and of then defending his harmful work, for three years, by the guiltiest and most absurd of machinations.

I accuse General Mercier of being an accomplice, if by weakness of spirit, in one of greatest iniquities of the century.

I accuse General Billot of having held in his hands the unquestionable evidence of Dreyfus's innocence and of suppressing it, guilty of this crime that injures humanity and justice, with a political aim and to save the compromised Chie of High Command.

I accuse General De Boisdeffre and General Gonse as accomplices of the same crime, one undoubtedly by clerical passion, the other perhaps by this spirit of body which makes offices of the war an infallible archsaint.

I accuse General De Pellieux and commander Ravary of performing a rogue investigation, by which I mean an investigation of the most monstrous partiality, of which we have, in the report of the second, an imperishable monument of naive audacity…

Finally, I accuse the first council of war [i.e., the first military court that convicted Dreyfus] of violating the law by condemning a defendant with unrevealed evidence, and I accuse the second council of war of covering up this illegality, by order, by committing in his turn the legal crime of knowingly discharging the culprit." [Meaning Major Esterhazy].

Clemenceau published the letter on the front page of L’Aurore on January 13, 1898.

As Zola hoped, it fueled increasing pressure to free Dreyfus. It was also a brave act of political activism. He was, in effect, taking on the French military and political establishment and he knew he would be targeted by them for revenge.

Almost immediately, Zola was charged with “criminal libel.” On February 23, 1898, he was convicted and sentenced to a year in prison. Zola refused to serve his jail time and fled to England.

But his “J’Accuse!” letter marked a major turning point in the Dreyfus Affair.

During the summer of 1899, the French military held another trial for Dreyfus and, despite the questionable evidence, found him guilty again. However, public sentiment had started to turn against them in France and around the world.

Anti-French demonstrations sprang up in twenty foreign capitals. Editorials in scores of newspapers in other countries decried the unfair treatment of Dreyfus.

Prior to the end of the second Dreyfus trial, President Faure died. On September 19, the new French President, Émile Loubet, gave Dreyfus a pardon. To save face for the French army brass, Loubet let Dreyfus’ conviction stand.

Thus, even though Dreyfus was allowed to return to France, he was still technically a convicted criminal and lived with relatives under “house arrest.”

Finally, on July 12, 1906, the French Supreme Court declared Dreyfus innocent of treason. He was readmitted to the army and promoted to the rank of major.

Dreyfus served throughout World War I, rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and was awarded the Legion of Honor.

He died in Paris at age 75 on July 12, 1935 — exactly 29 years after he was officially exonerated.

Like Dreyfus, Zola returned to France in 1899. He had lived long enough to see President Faure’s right wing government fall and to see the success of his efforts to secure the freedom of Alfred Dreyfus. But he died tragically before seeing the final vindication of his heroic public stand on the Dreyfus Affair. In 1902, he was asphyxiated in his bedroom by carbon dioxide gas caused by a blocked stove flue.

George Clemenceau lived to see his support for Dreyfus and many of his other political views vindicated. He became one of France’s most important political figures, serving as Prime Minister from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 to 1920. He died in 1929 at age 88.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page or send me an email.

Related reading and viewing…

Copyrights, Disclaimers & Privacy Policy

Copyright © Subtropic Productions LLC

All original text written for the This Day in Quotes quotations blog is copyrighted by the Subtropic Productions LLC and may not be used without permission, except for short "fair use" excerpts or quotes which, if used, must be attributed to ThisDayinQuotes.com and, if online, must include a link to http://www.ThisDayinQuotes.com/.

To the best of our knowledge, the non-original content posted here is used in a way that is allowed under the fair use doctrine. If you own the copyright to something posted here and believe we may have violated fair use standards, please let us know.

Subtropic Productions LLC and ThisDayinQuotes.com is committed to protecting your privacy. For more details, read this blog's full Privacy Policy.