I recently

“North Korean missile tests signal return to brinkmanship.”

The term brinkmanship was coined in 1956 during the height of the Cold War, when the U.S. was facing a potential nuclear war with two other Communist powers, the Soviet Union and Red China.

It’s often spelled as brinksmanship, with an s. That spelling reflects previous terms it was based on, such as the very old word sportsmanship and more recent word gamesmanship.

The latter was popularized in the late 1940s and early 1950s by British author Stephen Potter’s humorous, best-selling book The Theory and Practice of Gamesmanship: Or the Art of Winning Games Without Actually Cheating.

Potter didn’t coin the word gamesmanship. It was first recorded in Ian Coster’s autobiographical book Friends in Aspic, published in 1939.

Coster said he heard his friend Francis Meynell use it to describe sports behavior that involved “the art of winning games by cunning against opponents with superior skill.”

However, Potter’s Gamesmanship book made the term widely known and spawned other “-manship” terms.

Potter himself helped encourage that trend by writing follow-up books like Lifemanship in 1950 and One-Upmanship in 1952.

The word brinkmanship was inspired by controversy over a quotation that became both famous and infamous.

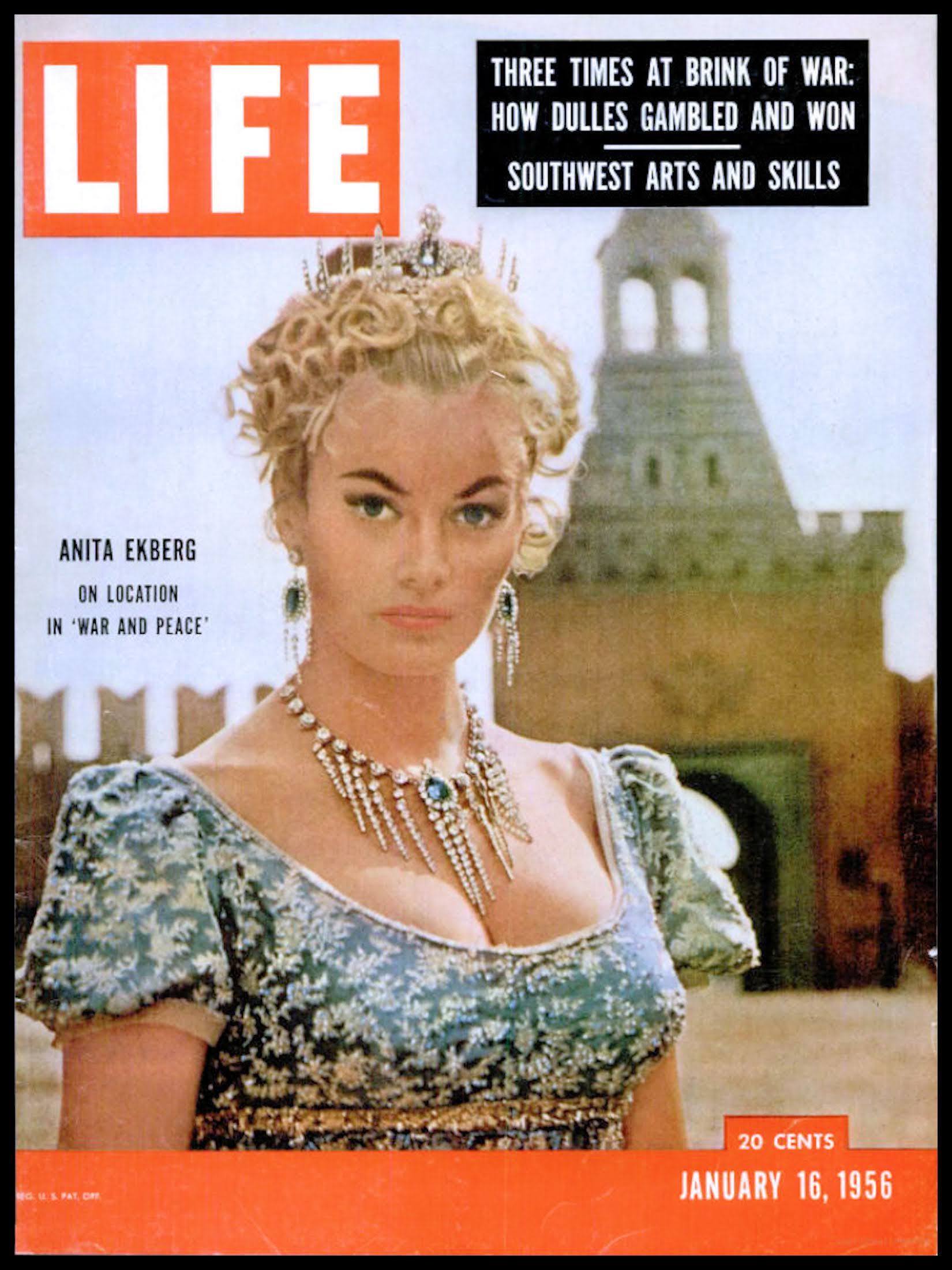

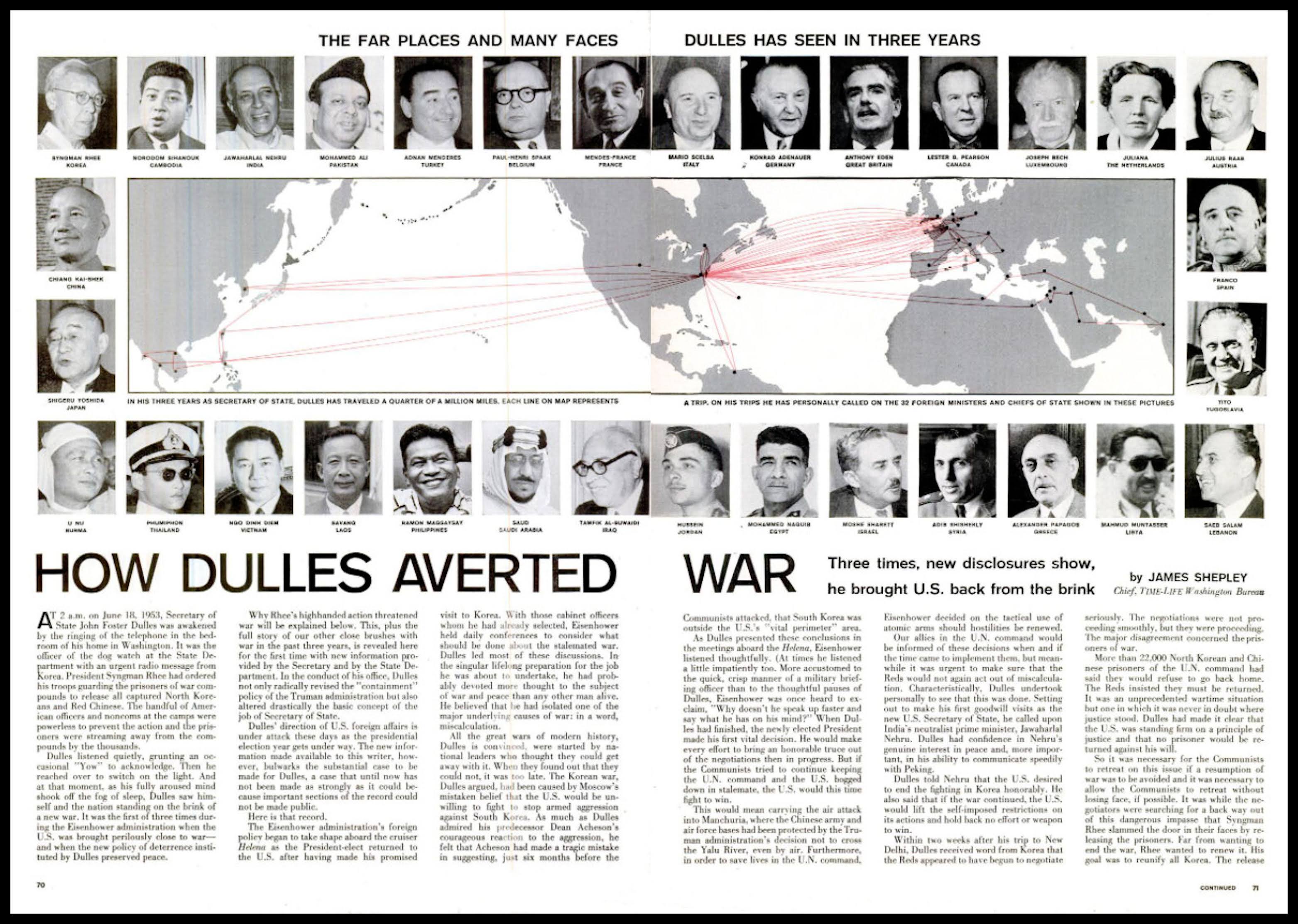

The quote appeared in an article about lawyer, politician, and statesman John Foster Dulles in the January 16, 1956 issue of Life magazine.

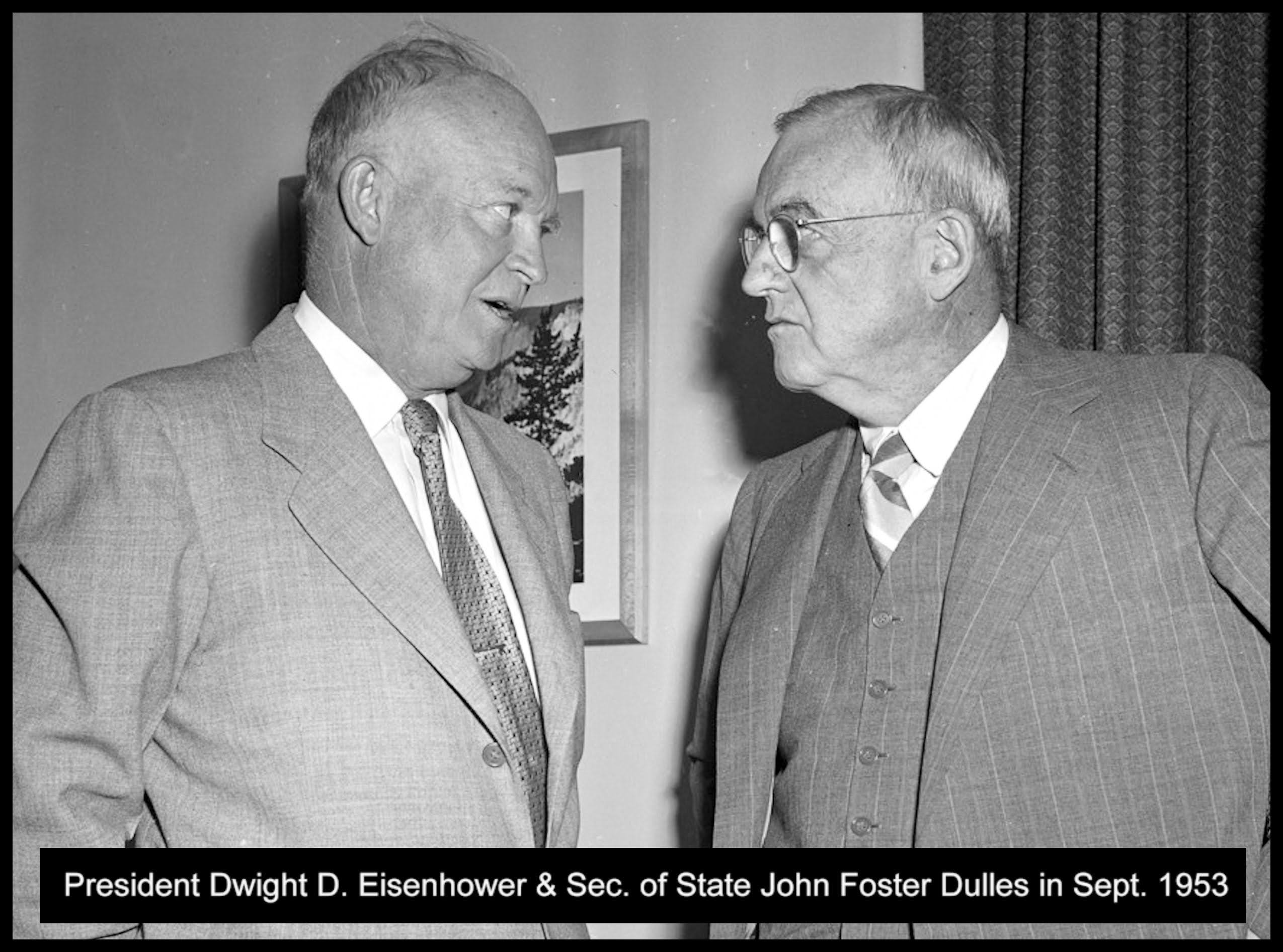

Since 1953, Dulles had been serving as U.S. Secretary of State under Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower. During that time, he’d dealt with a number of international political crises.

One of America’s fundamental Cold War polices was to try to prevent Communism from spreading to countries in Southeast Asia, South America and elsewhere. President Eisenhower memorably outlined that concern in a press conference on April 7, 1954.

As noted in a previous post on This Day in Quotes, Eisenhower described the threat of creeping Communism as the “falling domino principle,” soon described in the press as “the domino principle” or “the domino effect.”

Concern about the spread of Communism led to the Korean War in 1950, various other armed conflicts (eventually including the Vietnam War), and an arms race that made the risk of nuclear war a gloomy, omnipresent concern for decades.

An end to the Korean War was negotiated in 1953, the year Eisenhower became president. But during the next few years, the Eisenhower administration faced decisions about how to deal with other threats that arose through actions by the Soviet Union, Red China, and their political allies.

Those included a potential resumption of war with Red China in Korea and another potential war if Red China tried to invade Taiwan.

Eisenhower and his point man on international politics, Secretary of State Dulles, took a hard line on these and other issues involving Communist regimes.

They made it clear, publicly and through diplomatic channels, that America was willing to use what Dulles described in a speech on January 12, 1954 as “massive retaliatory power” — which clearly implied the possibility of nuclear war — to stop actions by Red China, the Soviet Union, or other actors who crossed certain political lines in the sand. (That quote by Dulles soon embedded the term “massive retaliation” into our language.)

The article about Dulles in the January 16, 1956 issue of Life discussed those and other tense situations Dulles had dealt with. It included an extensive interview with him about the tough approach he and Eisenhower took.

One of the quotes by Dulles in the article launched another new Cold War term. Speaking of the recent saber-rattling over Korea and Taiwan, he said:

“You have to take chances for peace, just as you must take chances in war. Some say that we were brought to the verge of war. Of course we were brought to the verge of war. The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is the necessary art. If you cannot master it, you inevitably get into war. If you try to run away from it, if you are scared to go to the brink, you are lost.”

That quote, with its use of the concept of going to “the brink” of atomic Armageddon as a strategy, generated considerable criticism, especially from political opponents of the Eisenhower regime.

The most notable attack came from Adlai Stevenson II. He was a prominent Democratic politician who served as Governor of Illinois and made several unsuccessful attempts to be elected President of the United States prior to his death in 1965.

In 1956, the Democratic Party tapped Stevenson as their presidential candidate to run against Eisenhower. In a speech at Hartford, Connecticut on February 25, 1956, Stevenson said:

“We hear the Secretary of State boasting of his brinkmanship—the art of bringing us to the edge of the abyss.”

That line was widely quoted in news stories and embedded the term brinkmanship into our language. Stevenson is generally credited with coining the word. It was clearly based on the then widespread use of the term gamesmanship and variations on it.

Around the same time as Stevenson’s speech, the great political cartoonist Herbert Lawrence Block, commonly known as “Herblock,” drew a cartoon that reflected his view of the brinkmanship strategy.

It shows Dulles pushing Uncle Sam toward the edge of a cliff labeled as "THE BRINK," as he says “DON’T BE AFRAID — I CAN ALWAYS PULL YOU BACK.”

If you’re interested in Cold War history, you can read a scan of the complete Life magazine issue with the article about John Foster Dulles via Google Books (here). The text is also posted in the Internet Archive (here).

As someone who was a kid in the 1950s and practiced “duck and cover” drills at school in preparation for a possible nuclear attack, I found it fascinating.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page or send me an email.

Related reading, watching & listening…

Never Let a Fool Kiss You or a Kiss Fool You: Chiasmus and a World of Quotations

Never Let a Fool Kiss You or a Kiss Fool You: Chiasmus and a World of Quotations The entries are organized under 25 genres. In addition to providing the names and source citations, many entries are followed by interesting commentary about their context and meaning.

The entries are organized under 25 genres. In addition to providing the names and source citations, many entries are followed by interesting commentary about their context and meaning.  Naturally, GreatOpeningLines.com includes many widely-known opening lines, like that one by Austen. But what makes the website even more fun and fascinating to me is that Grothe includes many that — while not necessarily famous — are thought-provoking examples of well-crafted lines that demonstrate the art of grabbing a reader’s attention and making them want to read on.

Naturally, GreatOpeningLines.com includes many widely-known opening lines, like that one by Austen. But what makes the website even more fun and fascinating to me is that Grothe includes many that — while not necessarily famous — are thought-provoking examples of well-crafted lines that demonstrate the art of grabbing a reader’s attention and making them want to read on.