How will Rap and Hip Hop songs by Black musicians that use the N-word and seemingly glorify the “thug life” be viewed 140 years from now?

I don’t know for sure, of course.

But I’m willing to guess there will be various conflicting views among people who are both Black and White.

That’s certainly the case for the 140-year-old old song “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny,” which was written by the pioneering African American musician James A. Bland (1854-1911) and copyrighted on August 5, 1878.

Bland was in his early twenties at the time. He’d written other songs and was a popular performer in one of the minstrel shows that were common entertainment for both Blacks and Whites at the time.

But “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” carried Bland to a new level.

It became a megahit and made Bland the first Black international music superstar.

Thanks to that fame, he broke many color barriers in the decades after the Civil War, such as having some of his music published under his own name.

He also helped pave the way for Black musicians and performers who followed him.

However, because Bland wrote and performed minstrel show music, originally sung in blackface makeup by white performers and later by black musicians (including Bland before he became famous), and because some of Bland’s songs romanticized the lives of American slaves, his legacy is mixed.

The controversy over “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” is the most notable case in point.

You have probably heard the phrase “carry me back to old Virginny,” which Bland’s song popularized (though it was borrowed from an older one).

You may also be familiar with the melody of Bland’s song.

However, few people know much about James Bland or know the full lyrics of the song.

And, unless you live in Virginia, you’re probably unaware of the modern political controversy about the song.

You’ll understand why it became controversial when you read the lyrics.

They’re written in the voice of a former slave who misses his life on the plantation and loved his “Massa” (i.e., the slave-owning master of the plantation).

Here they are, in their original colloquial form:

[Chorus] “Carry me back to old Virginny.

There’s where the birds warble sweet in the spring-time.

There’s where this old darkey’s heart am long’d to go.

There’s where I labored so hard for old Massa,

Day after day in the field of yellow corn;

No place on earth do I love more sincerely

Than old Virginny, the state where I was born.

[Chorus repeats]

Carry me back to old Virginny,

There let me live till I wither and decay.

Long by the old Dismal Swamp have I wandered,

There’s where this old darkey’s life will pass away.

Massa and Missis have long since gone before me,

Soon we will meet on that bright and golden shore.

There we’ll be happy and free from all sorrow,

There’s where we’ll meet and we’ll never part no more.

[Chorus repeats]

Bland himself was never a slave and wasn’t from Virginia. He was the son of a highly-educated, free Black man and was born in New York. His father, Allen Bland, moved the family to Philadelphia after graduating from Wilberforce College.

James attended Howard University but didn’t graduate. As a teenager, he’d fallen in love with the banjo and the minstrel music that was popular in the 1870s. By age 14 he was performing it.

By his early 20s, he was a featured member of a local minstrel show and writing songs for himself and other musicians. Among the notable songs he wrote during the ‘70s, in addition to his ode to Virginia, is “Oh! Dem Golden Slippers.” It became and still is the theme song for the famed Philadelphia Mummers Parade.

Bland’s talent and the huge success of “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny,” “Oh! Dem Golden Slippers” and other songs he wrote led him to be billed as “The World’s Greatest Minstrel Man” and “The Prince of Negro Songwriters.”

In 1881, after touring the United States, he spent 20 years performing to wide acclaim in Great Britain and Europe, where he gave command performances for Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales and other dignitaries.

At his peak, Bland earned the equivalent of hundreds of thousands per year in today’s dollars. By the end of the century, the popularity of minstrel style music had declined and his expensive, proto-rock star lifestyle had drained his resources. (One of his legendary purchases was a 4.75 carat diamond, the largest diamond ever worn by a Black performer at the time.)

In 1901, he returned to the U.S. After that, he wrote songs for one unsuccessful musical, then faded into obscurity.

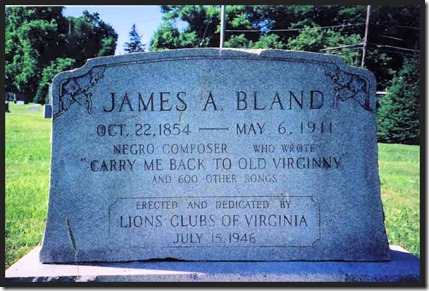

Bland died of tuberculosis in 1911 in Philadelphia. He was buried in an unmarked grave at Merion Memorial Park in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania.

James Bland’s story might have ended there if not for James Francis Cooke, editor of a magazine for musicians titled The Etude.

In 1938, Cooke became interested in Bland’s work. With the help of Bland’s sister, Cooke — or, according to some accounts, the Lions Club of Virginia or the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) — found Bland’s grave and eventually had a monument placed on it.

In 1939, Cooke published the first notable biography of Bland in The Etude. It was written by Dr. Kelly Miller, a noted African American scholar and professor at Howard University, who called Bland “The Negro Stephen Foster.”

The other lyrics remained as Bland wrote them, complete with the nostalgic “darkey” thinking fondly of his “Massa.”

As the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s gained traction, the song became a target of critics who (understandably) viewed it as racist and demeaning to African Americans.

In 1970, Douglas Wilder became the first African American elected to the Virginia Senate since Reconstruction. That same year, he proposed legislation to have the song retired and replaced.

The majority of White legislators, many of whom liked the rosy picture of slavery the song’s lyrics portrayed, rejected that bill and similar ones for years, including bills introduced after Wilder became the first African American to be elected Governor of Virginia — or any other state — in 1990.

Finally, in 1997, there was a compromise of sorts. The Virginia Senate voted to retire “Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” as the official state song, but designated it as the “State Song Emeritus” and authorized a study committee to create a contest to find and select a new state song.

To make a long story short, that approach continued to generate controversy for the next two decades.

It wasn’t until 2015 that a new state song was selected, based partly on the results of an online poll.

In fact, the legislature approved two songs as the new official state songs.

“Our Great Virginia,” a 19th Century ballad, was designated as the official “Traditional State Song.”

The song “Sweet Virginia Breeze” was named the official “Popular State Song.” It was written in 1978 by Richmond, Virginia musicians and Robbin Thompson and Steve Bassett, who included it on their 1978 album Robbin Thompson & Steve Bassett – Together.

Meanwhile, “Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” is still the “State Song Emeritus.” And, although many people can’t listen to the song without having a negative reaction, music scholars now consider James A. Bland to be not only “The World’s Greatest Minstrel Man,” as he was billed during his lifetime, but also one of the greatest black writers of American folk or popular songs.

In 1970, Bland was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

Every year since 1948, the Lions Clubs of Virginia has sponsored the annual Bland Music Scholarships Program’s “Bland Contest.” This program is designed is to promote cultural and educational opportunities for musically talented young people in Virginia by providing scholarships for college tuition, music lessons, summer music programs and other music education endeavors.

I watched YouTube videos of some of the young people who have performed in the Bland Contest in recent years. The music they played or sang tended to be more classical than popular.

But who knows? Maybe someday one of them could become as famous as James Bland was in his day, or write a song that becomes as revered — or reviled — as “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny.”

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page or send me an email.

Related reading…